René Guénon (1886-1951) is a singular and fundamental figure in the 20th-century intellectual landscape. A mathematician by training, his trajectory led him from the Parisian occultist circles of the early 1900s to becoming the foremost exponent and defender of the perennial philosophy or traditional intellectuality. After a spiritual crisis and a growing disillusionment with modern occultism, which he considered a degeneration of authentic esotericism, Guénon found in Eastern traditions, and finally in Islam (adopting the name Abdel Wahed Yahya), the pillars of his thought. His work, vast and rigorously coherent, constitutes a radical critique of the modern world, which he saw as plunged into an age of spiritual darkness (the Hindu Kali-Yuga), and a methodical exposition of the universal principles of the Primordial Tradition.

Principal Guénonian Ideas

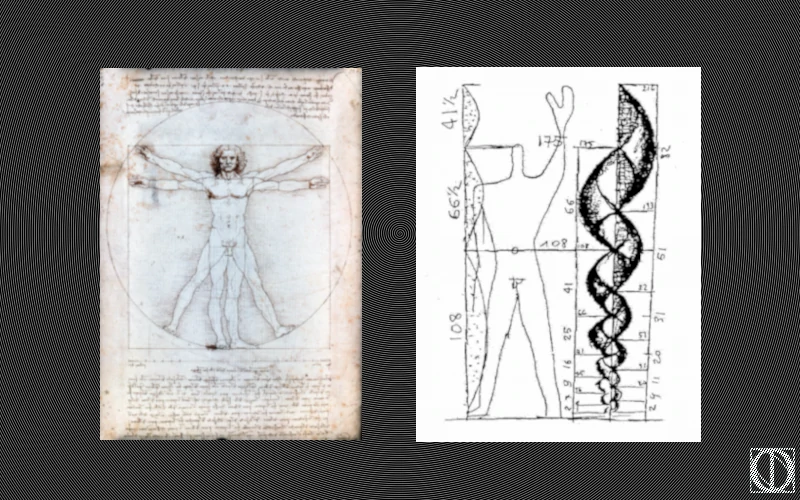

The core of Guénon’s thought is articulated around several key concepts. In opposition to modernity, characterised by materialism, rationalism, and individualism, Guénon posits the Unanimous Tradition: a primordial wisdom of non-human origin (revealed) that manifests through various traditional forms (Hindu, Taoist, Islamic, Christian, etc.). These forms are adaptations of a single metaphysical truth to particular historical and cultural conditions. He clearly distinguishes between exotericism (the domain of religion, law, and faith, accessible to all) and esotericism (the domain of direct spiritual realisation, reserved for a qualified elite seeking Gnosis or metaphysical knowledge). For Guénon, true intellectuality is not discursive reason, but pure Intellect, a faculty of intuitive and absolute knowledge of universal principles.

His Vision of Christian Hermeticism

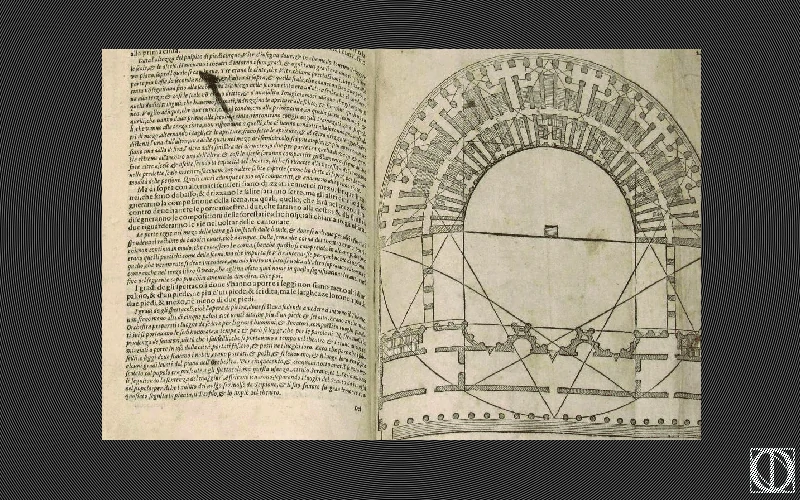

Guénon approaches Hermeticism, understood as the Western esoteric tradition linked to the figure of Hermes Trismegistus, from this perspective. He considers Hermetic doctrines to be an authentic expression of the Primordial Tradition, especially in its central principle of analogy (“As above, so below”). However, his analysis of Christian Hermeticism is particularly critical and nuanced.

Guénon maintains that in its origins, Christianity possessed a genuine esotericism, visible in the symbolic language of the Gospels (especially that of St. John) and in the writings of figures such as Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite. Nevertheless, he argues that this Christian esotericism became progressively obscured and lost in the West from the Late Middle Ages onwards. Scholasticism, by privileging rational theology (exoteric) to the detriment of mysticism and gnosis, and the condemnation of movements like the Cathars, would have provoked a “rupture” in the chain of initiatic transmission.

For this reason, Guénon views with scepticism most of the currents that, from the Renaissance onward, present themselves as “Christian Hermeticism” (later alchemists, Rosicrucian manifestos, etc.). For him, many of these manifestations are already contaminated by the modern spirit: they confuse true symbolism with literary allegory, tend towards sentimentality or practical “occultism” (magic, theurgy), and often lack a real connection to a legitimate initiatic organisation. Consequently, Guénon did not see a viable Christian esoteric path in modern Europe and for this reason, he turned his gaze towards the East, considering that Islamic esotericism (through Sufism) and Hindu esotericism (Advaita Vedanta) had preserved the principles of traditional metaphysics more intact.

In short, the Guénonian vision of Christian Hermeticism is that of a esotericism that is primordially valid but historically truncated, whose authenticity must be sought not in its modern developments, but in its purest sources and in its concordance with other sacred traditions.