Geometry is far more than a branch of mathematics; it is the foundational grammar of Western art and architecture. From its origins in antiquity to the radical innovations of the 20th century, this symbiotic relationship—oscillating between technical utility and profound symbolism—has been a primary engine of aesthetic innovation.

The Classical World: Geometry as Cosmic Order

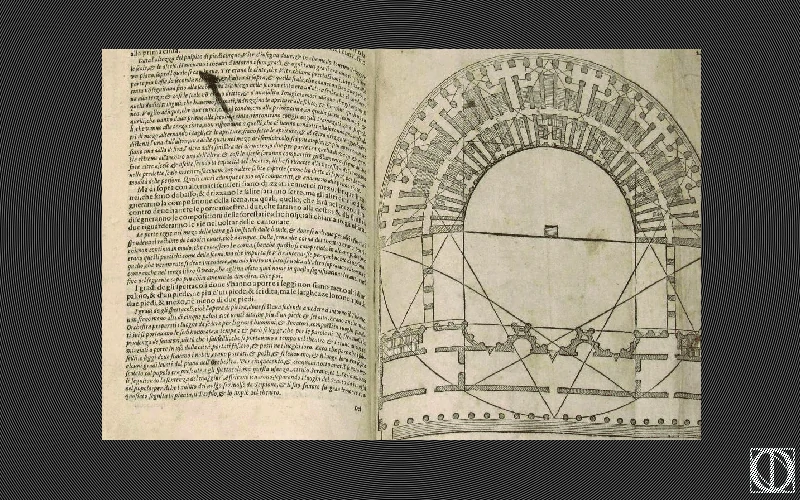

In classical antiquity, Euclidean geometry provided the language for an ordered and harmonious cosmos. The Roman architect Vitruvius, in his seminal treatise De Architectura (1st century BC), argued that architecture depended on two core geometric concepts: ordinatio (the system of proportions) and dispositio (the spatial arrangement of elements).

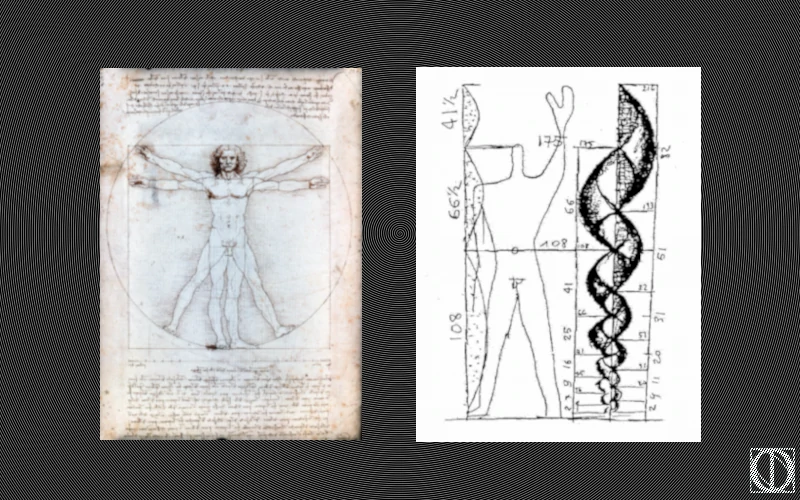

His vision was profoundly human-centric. The ideal human body, elegantly inscribed within a circle and a square—the Homo ad circulum and Homo ad quadratum—became the fundamental module for temple design. This philosophy was materialised in the Greek architectural orders. The Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian styles are not merely decorative; they are the physical expression of a universal geometry where every element maintains a precise, harmonious relationship with the whole.

The Gothic Ascent: Geometry as a Path to the Divine

During the Middle Ages, geometry’s purpose transcended the earthly to embrace the divine. The architects of Gothic cathedrals used sacred geometry—with the compass and square as their primary tools—to design structures that were symbolic models of a perfect divine cosmos.

Soaring vaults, intricate tracery, and vast rose windows were all conceived through complex geometric principles. Light itself, filtered through stained-glass windows arranged in geometric patterns, became a manifestation of lux divina (divine light). For theologians like Saint Augustine, geometry was the very language of God, and its study was a form of spiritual devotion.

The Renaissance: A Humanist Rebirth of Perspective

The Renaissance witnessed a rebirth of classical ideals, but through a newly humanist lens. Theorists and artists sought a scientific, mathematical basis for beauty.

- Leon Battista Alberti revived and expanded Vitruvius’s ideas.

- Luca Pacioli, in De divina proportione, exalted the Golden Ratio.

- Leonardo da Vinci‘s iconic Vitruvian Man became the enduring symbol of this fusion.

The crucial discovery was linear perspective. Based on projective geometry, it allowed for the first rational and verifiable representation of three-dimensional space on a flat surface. This revolutionised painting and solidified a new, anthropocentric view of the world, placing humanity at the centre of a geometrically ordered space.

The Modern Fracture: Geometry as Abstraction and Revolution

The 20th-century avant-gardes shattered the tradition of geometric harmony, repurposing its language for a new era.

- Cubism, pioneered by Picasso and Braque, decomposed reality into geometric facets, rejecting single-point perspective to present multiple viewpoints simultaneously.

- Neoplasticism, as championed by Piet Mondrian and De Stijl, reduced art to its essentials: straight lines, right angles, and primary colours. This was a quest for a pure, universal beauty, stripped of all anecdote.

In architecture, the Bauhaus and Le Corbusier embraced a functional, abstract geometry. Le Corbusier’s Modulor—a system of proportions based on the human form—was a direct, industrial-age attempt to revive the Vitruvian ideal for mass production and modern design.

Conclusion: The Unbroken Thread of Geometric Order

From the Parthenon’s columns to the crystalline forms of a Gothic cathedral and the fragmented planes of a Cubist canvas, geometry has been the constant, unbroken thread. It is more than a tool; it is an ordering principle, a symbol of the divine, a reflection of humanism, and a language of modern abstraction. This continuous dialogue stands as a testament to humanity’s eternal quest to impose order, meaning, and beauty upon the world we inhabit and create.