The 18th and 19th centuries constituted a period of scientific and popular fascination with the nature of visual perception, laying the technological and conceptual foundations for the invention of cinema. Far from being mere entertainments, so-called “philosophical toys” or “optical toys” were crucial instruments at the intersection of art, science, and spectacle, allowing for the exploration and harnessing of the perceptual principles that make the illusion of movement possible, primarily persistence of vision and the phi phenomenon.

The 18th century, imbued with the spirit of the Enlightenment, sought to rationalise vision. The Camera Obscura, known since antiquity, was refined as a tool for artists and scientific observers. However, the most significant advance was the popularisation of the Camera Lucida (1807), a prismatic device that projected an image of an object onto paper to trace its outline with precision. Although it did not create an illusion of movement, this instrument reflects the desire to capture reality objectively, a principle that would later be inverted with toys that created reality from illusion.

The true revolution arrived in the 19th century with the scientific exploitation of perception. It is crucial to distinguish between two fundamental principles that explained apparent motion. On one hand, persistence of vision (a concept popularised by Peter Mark Roget in 1824) posits that the eye retains an image for a fraction of a second after it has disappeared. This, it was believed, allowed successive static images to “fuse” into a continuous sequence. On the other hand, the phi phenomenon, later identified by Gestalt psychology, is a higher cognitive mechanism where the brain, upon perceiving visual stimuli in slightly different positions in rapid succession, generates the illusion of continuous movement between them. While persistence of vision prevents flicker (image fusion), the phi phenomenon creates the sensation of displacement (apparent motion).

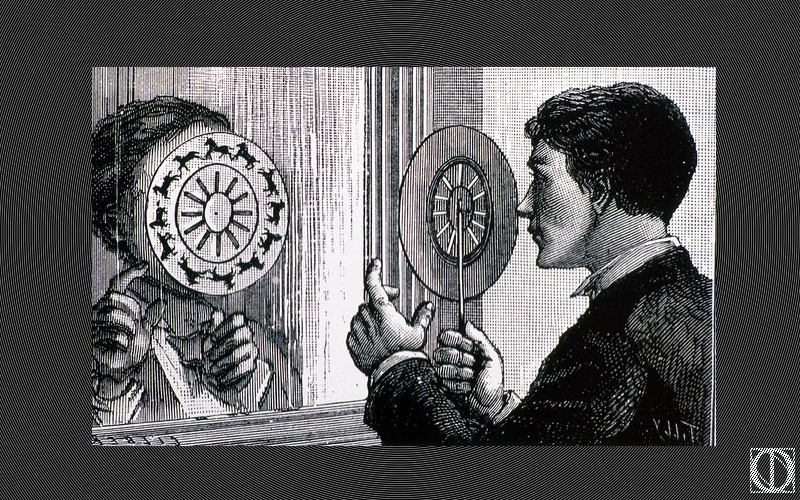

The Thaumatrope (1825), a disc with a picture on each side that fused when spun, demonstrated primarily persistence of vision. However, complexity increased with Joseph Plateau’s Phenakistiscope (1832) and Simon Stampfer’s Stroboscope. These devices, by showing drawings in successive phases of a movement through slots, exploited both principles: persistence smoothed the transition, but it was the phi phenomenon that truly generated the compelling illusion of animation.

The culmination was the Zoetrope (1834) and the more advanced Praxinoscope (1877) by Émile Reynaud. These toys, by presenting longer and more fluid animated sequences, relied fundamentally on the phi phenomenon to create coherent visual narratives, directly prefiguring the cinematographic experience.

In conclusion, these optical toys were not simple pastimes but laboratories of perception. By experimenting with persistence of vision and the phi phenomenon, they paved the way not only technically but also perceptually for cinema, educating a generation in the new language of moving images.